Hello 'Pussy' it's Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle and Pippi Longstocking:

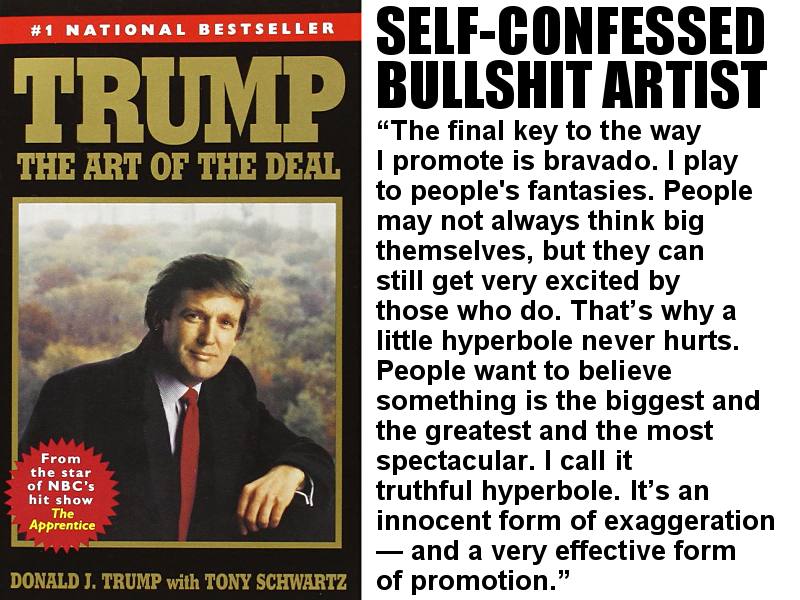

You appeared to acknowledge on Friday that your earlier tweet hinting of taped conversations with James B. Comey was intended to influence the fired F.B.I. director’s testimony before Congress.

Betty MacDonald fan club fans,

you can join Betty MacDonald fan club on Facebook.

Thank you so much in advance for your support and interest.I'm rereading Betty MacDonald's The Plague and I and although it's a very serious subject it's really so witty.

The book History of Firland, published by the sanatorium print shop in 1937, says: “The occupational therapy department is self-sustaining and not a burden to the tax payer.” Patients were often at the facility for a number of years, so vocational training and occupational therapy were crucial for a smooth reintroduction into society.

As you know Betty MacDonald didn't agree with this.

She hated occupational therapy.

‘Miss Gillespie was physically and

mentally exactly what you’d expect the producer of hand-painted paper

plates to be. She had a mouth so crowded with false teeth it looked as

if she had put in two sets … and her own set of rules. One of these

rules was that women patients could not use the basement lavatory

because “the men will see you go in there and know what you go

in there for”. Another forbade the pressing of men’s trousers by women,

on the grounds that such intimate contact with male garments was

unseemly.’

The Plague and I is my favourite book by Betty MacDonald.

Not to forget unique ' Kimi Sanbo ' our first Betty MacDonald fan club honor member Monica Sone, author of Nisei Daughter.

Enjoy a great Saturday,

Lona

The Plague and I is my favourite book by Betty MacDonald.

Not to forget unique ' Kimi Sanbo ' our first Betty MacDonald fan club honor member Monica Sone, author of Nisei Daughter.

Enjoy a great Saturday,

Lona

‘Anybody can have tuberculosis…’

THE PLAGUE AND I, by Betty MacDonald, originally published in in the UK in 1948, my edition 1959 (boy, do I love old Penguins)…

One of my favourites, for years and years. I can’t remember when I first encountered The Plague and I, but certain expressions and catchphrases from it have passed into our family shorthand, so my guess is that my parents loved it too.’Toecover’, for instance, a word that describes a hand-made object of uncertain usage and all-too-certain unpleasantness. Ideally, a toecover should have no discernible function, and – in my opinion – involve limp crochet in some respect. Then there’s ‘Hush ma mouth, what have ah said?’, delivered in a clichéd Southern accent. This should be deployed after the ostensibly inadvertent revelation of some fact that has got the speaker into trouble, and is ironically directed at the person who has given the game away. Then – no, enough already. You get the idea. This should not be a funny book. Absolutely not, no way, it’s about a stay in a 1930s tuberculosis sanatorium, for heaven’s sake – and yet it is. Hilarious, even laugh-out-loud funny in parts, and yet those parts are interspersed with more serious stuff. I recently lent it to a friend who had to spend some time in hospital, and she not only loved it, finding it funny too, but also found it relevant. As she said, ‘times change, but people don’t.’

In the late 1930s Betty MacDonald – who had led a slightly unconventional life but who had, as yet, not committed any of it to paper (her best-known book is probably The Egg and I, about her first marriage to a chicken farmer and which came out in 1945) – developed a series of colds, then a cough, then extreme tiredness… But, ‘operating under the impression that I was healthy and that everyone who worked felt the same as I did’, failed to put two and two together. In all fairness, so did a series of doctors (largely because she consulted each specialist about his – and I mean his – own area), until she was finally diagnosed with TB. Tuberculosis, of course, could be tantamount to a death sentence. As it can now, sometimes – but then there were no drugs which worked against it and it was horribly prevalent. It’s also highly contaigious and MacDonald caught hers from a co-worker who managed to infect several other people as well. As a single mother with two small children and a negligible income, she was luckily admitted to a charitable sanatorium in Seattle, which she calls ‘The Pines’ in the book. She was to stay at Firland Sanatorium for nine months, in 1938-9, and emerged cured.

The picture she creates is so vivid that this is one of those books where the mental images generated are so strong that they dominate even when you see contradictory pictures of the place that inspired them. The echoing, draughty corridors, the never-ending cold, the sound of invisible footsteps approaching, passing and then fading into the distance… but it’s not depressing, even in the serious phases. It’s populated by a cast of characters, all of whom I find exceptionally well drawn and entertaining. They range from Betty’s family and her near-constant companion in The Pines, Kimi Sanbo, to the miscellaneous array of nurses and other patients such as Gravy Face and Granite Eyes (two nurses); Charlie who loved to pass on depressing news of deaths and disasters; Minna of the Southern drawl and ability to dump people in the cacky… there are so many of them, so well delineated, that picking just a few to mention here was difficult. But space has to be made for Miss Gillespie of the Ambulant Hospital’s occupational therapy shop, generator of many a toecover:

So yes, a sort of happy ending. ‘Sort of’ because Betty MacDonald died in 1958, from cancer, at the age of only 49. I’m sure she would have been surprised and possibly flattered to know that people were still enjoying her books over fifty years later. I most certainly am. Great book.

One of my favourites, for years and years. I can’t remember when I first encountered The Plague and I, but certain expressions and catchphrases from it have passed into our family shorthand, so my guess is that my parents loved it too.’Toecover’, for instance, a word that describes a hand-made object of uncertain usage and all-too-certain unpleasantness. Ideally, a toecover should have no discernible function, and – in my opinion – involve limp crochet in some respect. Then there’s ‘Hush ma mouth, what have ah said?’, delivered in a clichéd Southern accent. This should be deployed after the ostensibly inadvertent revelation of some fact that has got the speaker into trouble, and is ironically directed at the person who has given the game away. Then – no, enough already. You get the idea. This should not be a funny book. Absolutely not, no way, it’s about a stay in a 1930s tuberculosis sanatorium, for heaven’s sake – and yet it is. Hilarious, even laugh-out-loud funny in parts, and yet those parts are interspersed with more serious stuff. I recently lent it to a friend who had to spend some time in hospital, and she not only loved it, finding it funny too, but also found it relevant. As she said, ‘times change, but people don’t.’

In the late 1930s Betty MacDonald – who had led a slightly unconventional life but who had, as yet, not committed any of it to paper (her best-known book is probably The Egg and I, about her first marriage to a chicken farmer and which came out in 1945) – developed a series of colds, then a cough, then extreme tiredness… But, ‘operating under the impression that I was healthy and that everyone who worked felt the same as I did’, failed to put two and two together. In all fairness, so did a series of doctors (largely because she consulted each specialist about his – and I mean his – own area), until she was finally diagnosed with TB. Tuberculosis, of course, could be tantamount to a death sentence. As it can now, sometimes – but then there were no drugs which worked against it and it was horribly prevalent. It’s also highly contaigious and MacDonald caught hers from a co-worker who managed to infect several other people as well. As a single mother with two small children and a negligible income, she was luckily admitted to a charitable sanatorium in Seattle, which she calls ‘The Pines’ in the book. She was to stay at Firland Sanatorium for nine months, in 1938-9, and emerged cured.

The picture she creates is so vivid that this is one of those books where the mental images generated are so strong that they dominate even when you see contradictory pictures of the place that inspired them. The echoing, draughty corridors, the never-ending cold, the sound of invisible footsteps approaching, passing and then fading into the distance… but it’s not depressing, even in the serious phases. It’s populated by a cast of characters, all of whom I find exceptionally well drawn and entertaining. They range from Betty’s family and her near-constant companion in The Pines, Kimi Sanbo, to the miscellaneous array of nurses and other patients such as Gravy Face and Granite Eyes (two nurses); Charlie who loved to pass on depressing news of deaths and disasters; Minna of the Southern drawl and ability to dump people in the cacky… there are so many of them, so well delineated, that picking just a few to mention here was difficult. But space has to be made for Miss Gillespie of the Ambulant Hospital’s occupational therapy shop, generator of many a toecover:

‘Miss Gillespie was physically and

mentally exactly what you’d expect the producer of hand-painted paper

plates to be. She had a mouth so crowded with false teeth it looked as

if she had put in two sets … and her own set of rules. One of these

rules was that women patients could not use the basement lavatory

because “the men will see you go in there and know what you go

in there for”. Another forbade the pressing of men’s trousers by women,

on the grounds that such intimate contact with male garments was

unseemly.’

Betty MacDonald is extremely good at expressing the life of any closed

institution. The way the world narrows down; the way rumours (‘all based

on a little bit of truth’) start, expand and spread; the effect of

being thrown into involuntary contact with people you would normally

avoid, and the intensity of the resulting reactions. (‘…the major

irritation of all was my room-mate, who was so damned happy all the

time, so well adjusted. She loved the institution and the institution

loved her. She loved all the nurses and the nurses loved her. She loved

all the other patients and all the other patients, but one, loved her.

That one used to lie awake in the long dark cold winter nights and

listen hopefully for her breathing to stop.’) It was a tough

regime, but it had to be – no drugs, remember. TB was essentially

treated by rest and some basic chest operations; there had to be rules.

But there was also the pointless expression of power indulged in by

some: ‘ “We do not tell the patients the rules, Mrs Bard. We find

that trial and error method is the best way to learn them.” I said, “But

how can I be obedient, co-operative, and helpful if I don’t know what

I’m supposed to do?” She said, “We don’t allow arguing, Mrs Bard”…‘

She is also very good on how difficult it is to adapt to life

afterwards, describing what could almost be a type of Stockholm

Syndrome. But she did shake herself free, and the TB didn’t reappear.

So yes, a sort of happy ending. ‘Sort of’ because Betty MacDonald died in 1958, from cancer, at the age of only 49. I’m sure she would have been surprised and possibly flattered to know that people were still enjoying her books over fifty years later. I most certainly am. Great book.

you can join

Betty MacDonald fan club

Betty MacDonald Society

Vita Magica

Eurovision Song Contest Fan Club

on Facebook

Vita Magica Betty MacDonald event with Wolfgang Hampel, Thomas Bödigheimer and Friedrich von Hoheneichen

Vita Magica

Betty MacDonald

Betty MacDonald fan club

Betty MacDonald fan club on Facebook

Betty MacDonald forum

Wolfgang Hampel - Wikipedia ( English )

Wolfgang Hampel - Wikipedia ( English ) - The Egg and I

Wolfgang Hampel - Wikipedia ( Polski)

Wolfgang Hampel - LinkFang ( German )Wolfgang Hampel - Wikipedia ( German )

Wolfgang Hampel - Academic ( German )

Wolfgang Hampel - cyclopaedia.net ( German )

Wolfgang Hampel - DBpedia ( English / German )

Wolfgang Hampel - people check ( English )

Wolfgang Hampel - Memim ( English )

Vashon Island - Wikipedia ( German )

Wolfgang Hampel - Monica Sone - Wikipedia ( English )

Wolfgang Hampel - Ma and Pa Kettle - Wikipedia ( English )

Wolfgang Hampel - Ma and Pa Kettle - Wikipedia ( French )

Wolfgang Hampel - Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle - Wikipedia ( English)

Wolfgang Hampel in Florida State University

Betty MacDonald fan club founder Wolfgang Hampel

Betty MacDonald fan club interviews on CD/DVD

Betty MacDonald fan club items

Betty MacDonald fan club items - comments

Betty MacDonald fan club - The Stove and I

Betty MacDonald fan club groups

Betty MacDonald fan club organizer Linde Lund

Betty MacDonald fan club organizer Greta Larson

Politics

Trump Indicates Tweet on Tapes Was Meant to Affect Comey Testimony