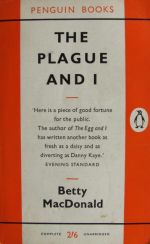

THE PLAGUE AND I, by Betty MacDonald, originally published in in the UK in 1948, my edition 1959 (boy, do I love old Penguins)…

One of my favourites, for years and years. I can’t remember when I first encountered The Plague and I,

but certain expressions and catchphrases from it have passed into our

family shorthand, so my guess is that my parents loved it

too.’Toecover’, for instance, a word that describes a hand-made object

of uncertain usage and all-too-certain unpleasantness. Ideally, a

toecover should have no discernible function, and – in my opinion –

involve limp crochet in some respect. Then there’s ‘Hush ma mouth, what

have ah said?’, delivered in a clichéd Southern accent. This should be

deployed after the ostensibly inadvertent revelation of some fact that

has got the speaker into trouble, and is ironically directed at the

person who has given the game away. Then – no, enough already. You get

the idea.

This should not be a funny book. Absolutely not, no way, it’s about a

stay in a 1930s tuberculosis sanatorium, for heaven’s sake – and yet it

is. Hilarious, even laugh-out-loud funny in parts, and yet those parts

are interspersed with more serious stuff. I recently lent it to a friend

who had to spend some time in hospital, and she not only loved it,

finding it funny too, but also found it relevant. As she said, ‘times

change, but people don’t.’

In

the late 1930s Betty MacDonald – who had led a slightly unconventional

life but who had, as yet, not committed any of it to paper (her

best-known book is probably The Egg and I, about her first

marriage to a chicken farmer and which came out in 1945) – developed a

series of colds, then a cough, then extreme tiredness… But, ‘operating

under the impression that I was healthy and that everyone who worked

felt the same as I did’, failed to put two and two together. In all

fairness, so did a series of doctors (largely because she consulted each

specialist about his – and I mean his – own area), until she was

finally diagnosed with TB. Tuberculosis, of course, could be tantamount

to a death sentence. As it can now, sometimes – but then there were no

drugs which worked against it and it was horribly prevalent. It’s also

highly contaigious and MacDonald caught hers from a co-worker who

managed to infect several other people as well. As a single mother with

two small children and a negligible income, she was luckily admitted to a

charitable sanatorium in Seattle, which she calls ‘The Pines’ in the

book. She was to stay at Firland Sanatorium for nine months, in 1937-8,

and emerged cured.

The

picture she creates is so vivid that this is one of those books where

the mental images generated are so strong that they dominate even when

you see contradictory pictures of the place that inspired them. The

echoing, draughty corridors, the never-ending cold, the sound of

invisible footsteps approaching, passing and then fading into the

distance… but it’s not depressing, even in the serious phases. It’s

populated by a cast of characters, all of whom I find exceptionally well

drawn and entertaining. They range from Betty’s family and her

near-constant companion in The Pines, Kimi Sanbo, to the miscellaneous

array of nurses and other patients such as Gravy Face and Granite Eyes

(two nurses); Charlie who loved to pass on depressing news of deaths and

disasters; Minna of the Southern drawl and ability to dump people in

the cacky… there are so many of them, so well delineated, that picking

just a few to mention here was difficult. But space has to be made for

Miss Gillespie of the Ambulant Hospital’s occupational therapy shop,

generator of many a toecover:

‘Miss Gillespie was physically and

mentally exactly what you’d expect the producer of hand-painted paper

plates to be. She had a mouth so crowded with false teeth it looked as

if she had put in two sets … and her own set of rules. One of these

rules was that women patients could not use the basement lavatory

because “the men will see you go in there and know what you go

in there for”. Another forbade the pressing of men’s trousers by women,

on the grounds that such intimate contact with male garments was

unseemly.’

MacDonald is extremely good at expressing the life of any closed

institution. The way the world narrows down; the way rumours (‘all based

on a little bit of truth’) start, expand and spread; the effect of

being thrown into involuntary contact with people you would normally

avoid, and the intensity of the resulting reactions. (‘…the major

irritation of all was my room-mate, who was so damned happy all the

time, so well adjusted. She loved the institution and the institution

loved her. She loved all the nurses and the nurses loved her. She loved

all the other patients and all the other patients, but one, loved her.

That one used to lie awake in the long dark cold winter nights and

listen hopefully for her breathing to stop.’) It was a tough

regime, but it had to be – no drugs, remember. TB was essentially

treated by rest and some basic chest operations; there had to be rules.

But there was also the pointless expression of power indulged in by

some: ‘ “We do not tell the patients the rules, Mrs Bard. We find

that trial and error method is the best way to learn them.” I said, “But

how can I be obedient, co-operative, and helpful if I don’t know what

I’m supposed to do?” She said, “We don’t allow arguing, Mrs Bard”…‘

She is also very good on how difficult it is to adapt to life

afterwards, describing what could almost be a type of Stockholm

Syndrome. But she did shake herself free, and the TB didn’t reappear.

So yes, a sort of happy ending. ‘Sort of’ because Betty MacDonald

died in 1958, from cancer, at the age of only 49. I’m sure she would

have been surprised and possibly flattered to know that people were

still enjoying her books over fifty years later. I most certainly am.

Great book.