60 Years Of Michael Jackson, The Fashion Icon

Michael Jackson

once recalled that whenever he’d watch James Brown dancing on TV during

his childhood, he’d shout at the screen in frustration when they didn’t

film his feet. He wanted to learn the moves. “If I had the chance to

talk to [Michelangelo],” he told Oprah Winfrey

in 1993, “I would want to know about what inspired him to become who he

is. Not about who he went out with last night, or why he decided to sit

out in the sun so long.”

A New Exhibition Celebrates The Legacy Of Michael Jackson

In my eyes, growing up a Michael Jackson

disciple, the art always went hand-in-hand with the artist, this

mythical creature seemingly of another world. From his fantastical face

to his fairy-dusted wardrobe, Michael had to look as superhuman as he

did to match his incomprehensible talents and the enigmatic phenomenon

he was. Watching his interviews, I had similar childhood experiences,

only I’d be shouting, “Ask him about his wardrobe!” Hung up on

scrutinising his eccentricities, they never did. On August 29th he would

have turned 60.

Michael Jackson performing at the Super Bowl halftime show in 1993.

Getty Images

“If fashion says it’s forbidden, I’m going to do it,” Michael wrote in Moonwalk

from 1988. Rather than drape himself in the latest runway fashions, he

largely commissioned his wardrobe from personal dressmakers, inspired by

history and art. And yet, what few people know is how well Michael knew

his fashion. “Not long before he passed, Michael personally called John Galliano

to request a bespoke Napoleon jacket,” Rushka Bergman tells me. A fine

art scholar turned creative director, she styled Jackson for a Bruce

Weber cover story for L’Uomo Vogue in 2007 and the two hit it off.

For

the last years of his life, she served as his full-time stylist, the

only one he ever had. It was Bergman who dressed Michael in the

pagoda-shouldered Balmain jackets by Christophe Decarnin – inspired by the star’s own fashion legacy – which became his wardrobe during the filming of This Is It, the rehearsal documentary shot for the tour that never was. She put him in Tom Ford tailoring, schoolboy Dior Homme looks, and gold embellished Givenchy.

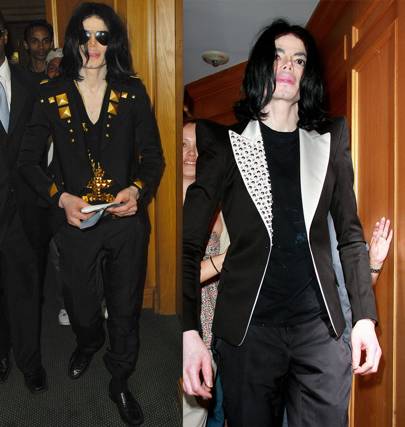

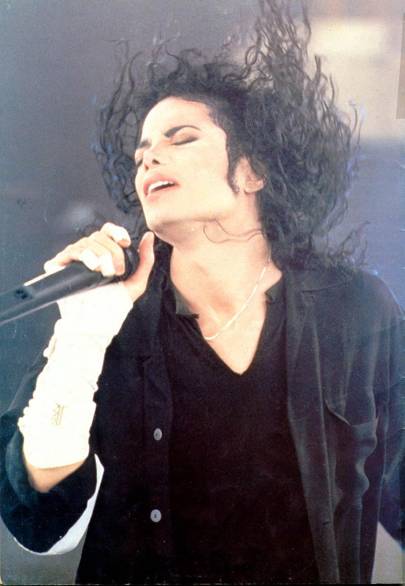

Michael

Jackson wearing a black and gold Givenchy jacket by Riccardo Tisci and a

black and silver Balmain jacket by Christophe Decarnin, both styled by

Rushka Bergman.

“Michael was an innovator so he wanted something new. He

challenged me to bring something fresh that no one had done before. My

goal was to bring back his status as a fashion icon,” Bergman recalls.

She was as familiar with his 1980s trademarks as anyone: “The beautiful

sequined glove, white socks, the military jackets, the red "Thriller"

leather jacket, sequined tuxedo pants, the penny loafers. His style was

so remarkable through his choices on stage,” she reflects.

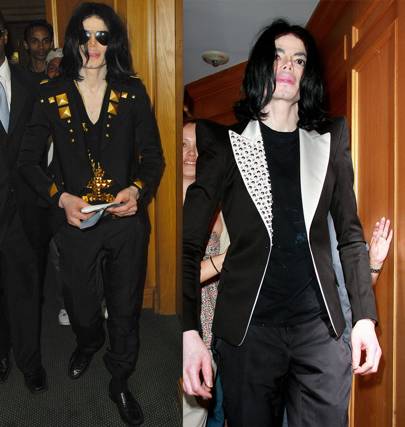

Michael Jackson in "Thriller".

shutterstock

“There was something very revolutionary in styling

Michael Jackson in clothes by haute couture designers. I moved him

forward with new avant-garde looks from the best designers in the world.

His favourites were Hedi Slimane, Tom Ford, Christophe Decarnin for Balmain, Riccardo Tisci for Givenchy, and Kris Van Assche for Dior Homme, and he especially loved John Galliano,” Bergman tells me, adding: “When I first started to work for him, he saw my Balenciaga gladiator flat studded sandals by Nicolas Ghesquière and begged me for two years to find them in his size!”

Through the 1990s, Jackson had occasionally worked with stylists from the fashion world on one-off music videos. British Vogue’s fashion director Venetia Scott styled 1993’s "Give Into Me" in slick rock‘n’roll, stylist David Bradshaw got him into Dexter Wong and Ann Demeulemeester for "Scream" in 1994, and in 1992 Jackson danced with Naomi Campbell in little more than a white tank top and black jeans for the Herb Ritts-directed "In the Closet".

Through the 1990s, Jackson had occasionally worked with stylists from the fashion world on one-off music videos. British Vogue’s fashion director Venetia Scott styled 1993’s "Give Into Me" in slick rock‘n’roll, stylist David Bradshaw got him into Dexter Wong and Ann Demeulemeester for "Scream" in 1994, and in 1992 Jackson danced with Naomi Campbell in little more than a white tank top and black jeans for the Herb Ritts-directed "In the Closet".

Michael Jackson and Janet Jackson in "Scream" styled by David Bradshaw.

youtube

But it was the never-ending supply of encrusted military

jackets and regalia that defined his signature look. “Michael was

infatuated with British hereditary and military history,” Michael Bush

writes in his book The King of Style: Dressing Michael Jackson.

From 1985 onwards, he and partner Dennis Tompkins served as personal

dressmakers to the King of Pop. “Liberace goes to war,” they

mischievously coined his look: magnificent military jackets covered in

soutache and bullion embroideries, topaz and rhinestone. Michael, who

proudly owned his Peter Pan syndrome, referred to surface decoration as

“dust”: pure magic, the Tinker Bell way.

Michael Jackson in the music video for "Give Into Me" styled by Venetia Scott.

“One of Michael’s favourite quotes came from an

unexpected source: ‘It is with such baubles that men are led.’ Napoleon

had said these words to indicate the significance of the medals with

which he regaled his soldiers,” Bush writes. “When we toured in Europe,

Michael made it his business to visit castles and ancient cities, where

he was mesmerised by museum portraits of kings and queens.” In 2009,

Bush and Tompkins buried their boss in a replica of his favourite-ever

garment, the Pearl Jacket he wore to the Grammys in 1993.

“For

Michael’s costumes, Dennis and I studied monarchs and European military

history, taking particular notice of one of the most notorious kings,

King Henry VIII of England. And there they were,” Bush writes. “Pearls.

Sewn on the king’s clothes, bedazzling his collars, vests, and bibs.”

After another Bush, President George H. W., presented him with the

Entertainer of the Decade honour in 1990, Michael thought he’d treat

himself. He showed his dressmakers a picture of the Queen’s Imperial State Crown, and off they went to the Tower of London to study the real deal.

Michael Jackson and Janet Jackson at the 1993 Grammys.

shutterstock

Tompkins taught himself how to solder and sandblast

metal and, over six weeks, created a sterling silver crown encrusted

with costume stones and pearls. In place of the Second Star of Africa –

which sits at the centre of the Imperial State Crown – Tompkins

sandblasted an imitation diamond with the iconic image of Michael’s

dancing feet. He never wore the crown out, but years later his children

asked Bush and Tompkins to make a regal robe for their dad to wear on

Father’s Day, and so – alongside the throne that stood in his en suite

bedroom at Neverland – the King of Pop’s ceremonial dress was complete.

Bergman recalls how Jackson related his sense of dress to history and

music.

“One of the first questions he asked me was

what period of art I liked best. I told him I loved the 16th century

Renaissance. He said, ‘That’s why we have so much in common.’ He loved

Baroque, and you could see the inspiration in his clothes. He was

noble,” she reflects. “That day, Michael taught me about baroque music

and then the styles of European classical music by composers such as

Bach, Vivaldi, Monteverdi and Händel. He absolutely loved Tchaikovsky.”

Michael Jackson's crown by Bush and Tompkins.

Getty Images

In the hall of Neverland stood a miniature castle

similar to Neuschwanstein in Bavaria, the neo-gothic Wagner dream built

by the reclusive and escapist King Ludwig II with whom Michael had so

much in common. Around it hung portraits of Michael painted as kings and

arch angels, and the last he commissioned was to be his masterpiece:

Michael painted as Philip III on horseback after Rubens’ fairy-tale

depiction, interpreted through the eye of Kehinde Wiley.

You

could put Jackson’s desire for grandeur down to aspiration or even

megalomania, but while he fashioned himself in the images of great

rulers – and sometimes even religious icons – he reminded us, “I am just

like anyone. I cut and bleed.” More than anything, his wardrobe and the

portraits he commissioned of himself reveal a search for answers to the

question: why me? Why was he gifted with such an extraordinary

existence? Speaking at Oxford University in 2001, he quipped, with some

solemnity, “I’ve always felt a kinship with Kermit’s message that it’s

not easy being green.”

A portrait of Michael Jackson.

ALAMY

He would cry at the true story of the Elephant Man,

Joseph Merrick, a highly sophisticated individual masked with the

Proteus syndrome that turned him into a sideshow for public ridicule in

the late 19th century. Before Michael developed vitiligo – his own

otherworldly condition, which, with the aid of makeup, would eventually

invert the colour of his skin – he went through adolescence at the

height of childhood fame, his changing looks scrutinised by media.

Michael Jackson wearing Dior Homme by Hedi Slimane, with Rushka Bergman on the L'Uomo Vogue shoot in 2007.

The physical changes and procedures he went through

turned him into an immaculate conception: to the eye he was ageless,

almost genderless and racially ambiguous. In turn, he became universally

relatable: a genius dancer and musician, yes, but a man whose physical

presence encompassed every age, gender, race and sexuality. Our current

zeitgeist considered, he was lightyears ahead of his time. Somehow, the

grandeur with which he staged himself must have helped him to understand

his exceptional and no doubt lonely place on Earth.

“Michael was a perfectionist. He knew exactly what he liked and didn't like,” Bergman tells me. “Since he was the King of Pop, he needed the best people in the world working for him and he was very specific as to whom. He was always the conductor. At the same time, he was a great father and a true humanitarian. His heart was bigger than the planet; even bigger than the galaxy. His gentle and spiritual nature made him one of the greatest people to ever walk the Earth.”

“Michael was a perfectionist. He knew exactly what he liked and didn't like,” Bergman tells me. “Since he was the King of Pop, he needed the best people in the world working for him and he was very specific as to whom. He was always the conductor. At the same time, he was a great father and a true humanitarian. His heart was bigger than the planet; even bigger than the galaxy. His gentle and spiritual nature made him one of the greatest people to ever walk the Earth.”

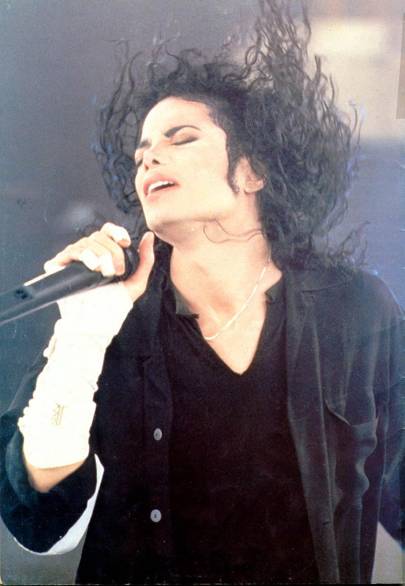

Michael Jackson performing in Paris in 1988.

Getty Images

Today, Bergman is creative director for Michael’s daughter Paris Jackson,

serving the princess the way she did the king. “As much I know him, as

much as I love him, it was magic. He was so beautiful. The power of

love,” she reflects. “I miss him very much and I will never forget him.”

Whether you remember Michael Jackson for his music, his performances,

his sense of style or the full package that encompassed his art, the

unbelievable thing isn’t that we lost him nine years ago, but that we

ever had him in the first place.