Linde Lund shared Dreamworld's photo.

Betty MacDonald fan club fans,

Betty MacDonald fan club newsletter February is really one of the best ones so far in Betty MacDonald fan club history.

It's a fact that Betty MacDonald fan club got outstanding Betty MacDonald fan club honor members from all over the world.

That's one of the reasons why Betty MacDonald fan club is so successful and lively.

Thank you so much for your great ideas and outstanding support dearest Betty MacDonald fan club honor members Monica Sone, Darsie Beck, Gwen Grant, Letizia Mancino, Perry Woodfin, Mary Holmes, Bernd Kunze, Tracy Tyne Hilton, Tatjana Geßler, Thomas Bödigheimer and one and only Betty MacDonald fan club honor member Mr. Tigerli.

Of course we shouldn't forget to praise unique Betty MacDonald fan club founder Wolfgang Hampel, Betty MacDonald fan club organizer Linde Lund and our excellent Betty MacDonald fan club research teams!

Thanks a million!

Betty MacDonald fan club birthday card contest will be great.

Therefore join us, please.

Betty MacDonald described this guy in each of her biographical books.

So what, Bengt? That's a very good advice, isn't it.

Send us the names please and maybe you'll be our next Betty MacDonald fan club contest winner.

Wolfgang Hampel's Betty MacDonald and Ma and Pa Kettle biography and Betty MacDonald interviews have fans in 40 countries. I'm one of their many devoted fans.

Many Betty MacDonald - and Wolfgang Hampel fans are very interested in a Wolfgang Hampel CD and DVD with his very funny poems and stories.

We hope to hear from Betty MacDonald fan club honor member Mr. Tigerli very soon.

Betty MacDonald fan club honor members will be included in Wolfgang Hampel's new project Vita Magica.

Wolfgang Hampel's next Vita Magica guest is a famous politician.

Enjoy a new breakfast at the bookstore with Brad and Nick, please.

Betty MacDonald's Vashon Island is very beautiful.

I enjoy this video very much.

Brigitte I do agree: This song could be next ESC 2016 winner.

Take care,

Ruud

Vita Magica

Betty MacDonald fan club

Betty MacDonald forum

Wolfgang Hampel - Wikipedia ( English )

Wolfgang Hampel - Wikipedia ( German )

Wolfgang Hampel - Monica Sone - Wikipedia ( English )

Wolfgang Hampel - Ma and Pa Kettle - Wikipedia ( English )

Wolfgang Hampel - Ma and Pa Kettle - Wikipedia ( French )

Wolfgang Hampel in Florida State University

Betty MacDonald fan club founder Wolfgang Hampel

Betty MacDonald fan club interviews on CD/DVD

Betty MacDonald fan club items

Betty MacDonald fan club items - comments

Betty MacDonald fan club - The Stove and I

Betty MacDonald fan club organizer Linde Lund

Linde Lund shared Sarai Sarai's photo.

Mr. Tigerli's memories

Copyright 2015 by Letizia Mancino

Translated by Mary Holmes

All rights reseverd

My birthday!

I, Mr. Tigerli, can hardly save myself

from being submerged in red roses! Oh dear, a loving cat has his

problems.

Surrounded by a sea of flowers!

Mind you I’ve earned it. I have risked so much for love in my life!

I have become famous because of being such a great lover. I am a Casanova cat.

Am I exaggerating? Are there not cats more famous than me, artists who paint or play the piano?

That may be so, but they are “nobodies” in the art of loving!

Look in the internet under “Erotica Felina”! You will see that my name immediately appears on the screen.

People boarding their plane in Singapore have found me at once on Google.

I am a world famous cat.

Oh

no, I don’t loose my head over female cats. But women! I love women.

Yes only women. These wonderful creatures give me everything! Not only

affection, good conversation and food.

I was four months old when I discovered my partiality for women.

One

time I was cavorting on the bed with Roswitha, my first love – although

it was strictly forbidden to get onto the bed – when under the woolen

blanket I suddenly felt a wonderful soft plump area! Roswitha’s tummy! I

was running backwards and forwards across it when suddenly a shot of

adrenalin rushed through my cat brain. At an early age I became a slave

to love!

But

it was Roswitha’s foot that surprised me with my first erotic feelings.

She had unknowingly stretched it out of the bed under the pressure of

my four paws and for the first time I saw the naked foot of a woman.

Five small tempting little sausages attracted my attention. How

delicately the points moved. They were more attractive to look at than

the mice in the fresh grass. I miaowed to them “I’m going to bite you”!

I understand men who kiss the feet of women so ardently.

I immediately lost my head and my innocence.

Now I began to nibble at these five little porkies.

Roswitha

continued to sleep and sighed softly. Encouraged I licked her whole

foot. Roswitha laughed sweetly and delightfully in her sleep.

Within eight months I was familiar with her leg.

I

love beautiful legs. Without hair, without ticks or other insects. They

have such a wonderful perfume. I could lick women’s legs without any

saliva. Wonderful! A refined lover begins with delicate movements, not

by taking the female creation by storm. Only goats climb on the back of

their females without paying a single compliment. You know, Betty, that

a Casanova doesn’t come straight to the point!

Roswitha,

I love you Oh, my first love! I felt so good in your bed. I lay at your

feet in the night. But after two intimate years deeply in love with

your feet, your husband came home. His field service away from home was

over, and sadly my home service with you too.

“Get

out of my bed”, he shouted. It’s not right to treat a loving cat so

rudely, even when men have the right to be jealous of us. We are after

all superior to them. We are supple and seductively beautiful until old

age. We are not rude or, even worse, drunkards! A woman can spend

romantic hours stroking us or even sleep with us in her bed and still

believe in platonic love, which is hardly possible for them with a man.

Women never become pregnant with us and this has advantages. Casanova

was the inventor of the condom. We are the condom.

I

was thrown out. Are men all so brutal, Betty? The bedroom door was

locked. But I was still allowed to live in the house: three sofas in the

living room, a bed in the guest bedroom, and an old divan in the cellar

were available for me. Roswitha could come to these. But I was

appalled!

Mr. Brummi avoided my dirty looks. Since then I have not befriended men, to say nothing of cats!

Without Roswitha’s feet I had to eke out a miserable existence in the house. And she complained that her feet were cold.

The

husband however was obdurate. He tried, without success, to take my

place: to stroke Roswitha’s feet, to rub them, to tickle them! But

Roswitha’s five little white toes remained in the bed as motionless as

if rigor mortis had set in.

There

were no more giggles. The doctor recommended an evening foot-bath. To

think that I should be replaced by a herbal bath! How outrageous!

Should

I have scratched at the bedroom door every night? I am a proud cat! I

would rather look around! She wouldn’t have heard me anyway. The husband

snores as loudly as a vacuum cleaner on the point of collapse. Should I

have dropped five dead mice in front of the door? But I don’t bring her

these presents any more. If you love me, I thought, get divorced!

“Darling” I hear her say to her husband, “Couldn’t you snore more quietly?”

I

comforted myself with her socks. The dirty ones, naturally. There were a

few flakes from her skin that I swallowed with joy. Some men even sniff

underwear. Idiotic love. That’s going too far for me. I, Mr Tigerli,

don’t do that because I am an aesthetic cat. Gradually I’d had enough of

the socks. Should I look for a new woman? The thought of being

unfaithful came to me quite suddenly.

The

nights in my basket passed peacefully - and also the nights in

Roswitha’s bed. Cold feet and migraines are two passion killers. The

husband was sullen. She never suffered with me. I laughed - even if cats

can’t laugh – behind my beard and knew that she had remained faithful.

I didn’t. I found the young servant in the house very fascinating. Her

legs were not so beautiful as Roswitha’s , but the risks were low. The young

woman was a Russian, temperamental, pretty and I liked her. Infidelity

was for me a triviality.

“Oh, Mr. Tigerli”, cried

Putziputzi (that was her pet name. I’ll say no more, she had two

brothers) “why are you licking me so tenderly?”

I could have answered. “You are my

second choice. I am missing Roswitha’s feet.” But I wrapped myself

round her leg, as all loving cats do.

She gave an even louder cry and ran away! I was perplexed!

I had no idea that genuine love-play begins with “No, no, I’d rather not, please don’t”.

I still had a lot to learn. Then I

thought: Quick , Tigerli, follow Putziputzi and sing her a song! After

that wonderful days followed: I showered her soft thighs with delicate

little love-bites. It was intoxicating!

We constantly changed the spot we

chose for our love-making. On Mondays and Fridays we lay on the three

sofas, on Tuesday on the bed in the guest room, but most of the time we

spent together in the cellar. She was crazy! Is this sex,

I asked myself. What man can make a woman so happy?

Putziputzi was soon dismissed from her job.

I have no great opinion of

husbands and I must admit I have good reasons for this. But that their

wives should react with such jealousy was for me an insoluble puzzle.

It wasn’t long before I was lying in bed with Roswitha again.

The husband had probably seen that

the loss of a servant can have serious consequences. Now it was his job

to vacuum the whole house: from the cellar to the attic. Roswitha

assured him this would only be for a short transitional period, until

she had found a replacement for Putziputzi.

“Yes, yes! But the replacement

must be ugly and unattractive and she should only work in the house and

she must not play with Tigerli”, he answered.

“Yes, yes! I agree”, answered Roswitha, “and it would be wise if you would allow Tigerli to sleep in the bed with me again”.

The husband willingly gave his consent.

He nodded his agreement and it was clear that he saw me in a new light.

I was no longer a competitor.

What the heck, he thought! The guy was sleeping in my bed with my wife when I was away anyway!

So thanks to the vacuum-cleaner I was able to continue my love-affair with my first love Roswitha.

Germany and refugees

Is the welcome culture legal?

Under pressure to reverse her refugee policy, Angela Merkel faces a court case

Tying her hands

The argument that Mrs Merkel’s “welcome culture” is not only naive but downright illegal is popular among German conservatives. Proponents include eminent jurists such as Hans-Jürgen Papier, a former president of the constitutional court (and a member of the CSU). Claiming asylum in Germany is technically impossible for anybody arriving on a land route, he points out. Under the German constitution, since an amendment in 1993, protection is not available to people entering from “safe” states, a description that fits all nine of Germany’s neighbours.

Another former judge on the constitutional court, Udo di Fabio, goes a step further. Approached by Bavaria for a legal opinion on the suit, he concluded that it could win. His argument—which will sound more familiar to Americans than to citizens of more centralised states—is based on German federalism.

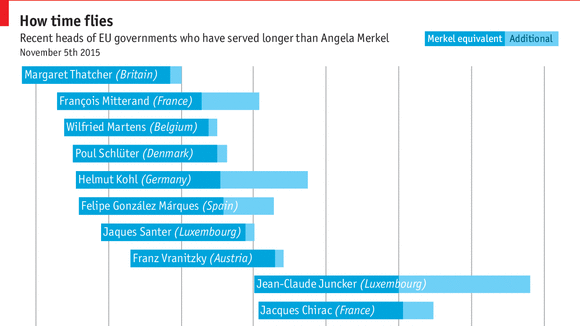

How do Angela Merkel's 10 years in office compare to other European heads of state?

In the Federal Republic of Germany, the nation, its 16 states and its

municipalities all have their own forms of “statehood”, as well as

obligations to one another. In the refugee crisis, these divisions and

responsibilities have become muddled. Federal agencies control the

external borders and decide on asylum claims. But the states provide

accommodation and social services, as well as deporting rejected

applicants. If the federal government neglects its role by allowing

chaos on the borders and an uncontrolled inflow of people, this could

undermine the statehood of Bavaria, say, by compromising its ability to

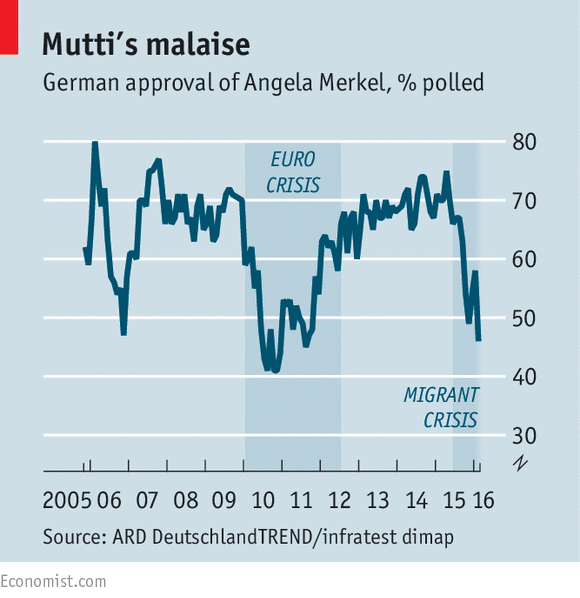

provide public safety and other functions.Germany’s constitutional court, unlike America’s, does not make a habit of resolving political disputes, and may not take such a hot-potato case even if Bavaria files it. But spelling out the legal logic exerts great political force. Mrs Merkel governs in a partnership between her Christian Democrats, the centre-left Social Democrats and the CSU. Mr Seehofer’s legal threat amounts to “a declaration of breaking the coalition”, says a top Social Democrat. At a pinch, Mrs Merkel could govern without the CSU. But given her waning popularity (see chart), she may not wish to. In fact, she has already been tightening asylum law piecemeal. Should she decide to close Germany’s borders to refugees for political reasons, her critics’ legal argument might serve as a handy excuse.

View all comments (104)Add your comment