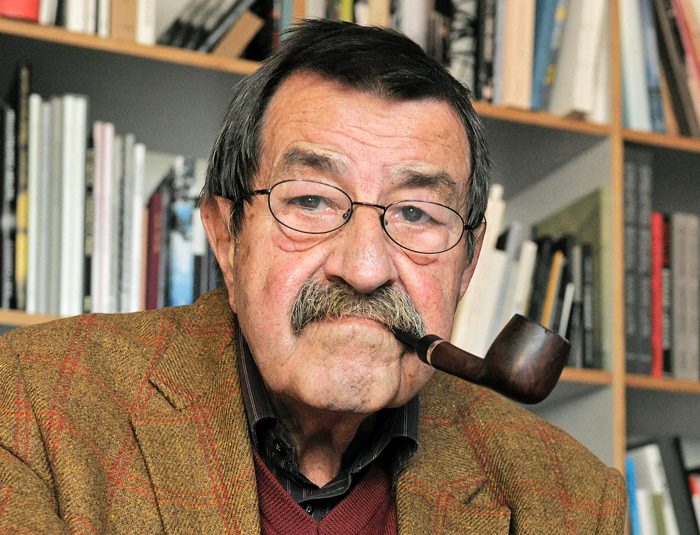

Günter Grass, Nobel-winning novelist dies aged 87

Author of The Tin Drum passes away in hospital in Lübeck

Günter Grass, who received the Nobel Prize for literature in 1999, has died aged 87. Video: Reuters

Germany’s celebrated and controversial Nobel Prize-winning author Günter Grass has died aged 87.

His

1959 debut novel ‘The Tin Drum’ established Mr Grass’s reputation as

one of West Germany’s leading public intellectuals and pacifist voices.

But

his reputation as a writer - and as a moral authority - suffered in

later years after he admitted volunteering for the Waffen-SS.

The Irish Times takes no responsibility for the content or availability of other websites.

Grass was born in 1927 in what was then the free city of Danzig, today Gdansk, in Poland, where his parents ran a shop.

A

biographer later described his Catholic upbringing in Danzig, a hotbed

of Nazi agitation, as trapped “between the Holy Spirit and Hitler”.

As

a 17 year-old in 1944 he served first as a flak helper then in the

Waffen-SS. He was injured and held as a prisoner-of-war until 1946 in

Bavaria. He moved to Düsseldorf to study art and played in a jazz band

until 1952.

He remained an active painter

throughout his life but, after moving to Paris in 1956, his visual art

was eclipsed three years later with ‘The Tin Drum’.

Filmed

in 1980 by Volker Schlöndorff, it was the first part of his ‘Danzig

Trilogy’, which attracted a huge following - and no share of controversy

- for his energetic language and provocative anti-war message.

As

well as political novels, he wrote poetry and plays and published

collections of essays. From 1965 on became a regular voice in West

Germany’s political scene as a staunch electoral supporter of Willy

Brandt and his Social Democratic Party (SPD).

After decades of success, his latter years were an unhappy professional time for Grass.

Novels

in the 1990s were given vicious reviews and many never understood, nor

forgave, his warning against a “rushed” German unification.

His

final controversial novel, 1999’s ‘Crabwalk’, looked at the 1945

sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff liner with 10,000 passengers - mostly

German civilians - onboard.

Many welcomed his

breaking of the taboo of discussing German victims of the second World

War but his reputation took a serious blow in his 2006 autobiography,

‘Peeling the Onion’.

Here he admitted for the

first time that he had covered up part of his war record: his service in

the 10th tank division of the Waffen SS in Dresden. He said he had seen

no atrocities and had signed simply up to get away from home.

“My silence over the years is the reason I wrote this book, it had to come out, finally,” he wrote.

While

he attracted some praise, his critics pounced on the belated revelation

as proof that the man who devoted his life to “writing against

forgetting” was a hypocrite.

He divided German opinion one last time in the April 2012 poem ‘What Needs To Be Said’.

Published

simultaneously in three European newspapers, Grass accused Israel of

endangering world peace with its threat of a nuclear attack “that could

erase the Iranian people”.

Israel’s ambassador to Germany accused him of having a “disturbed relationship” to the country.

His

final book, published in 2010, was ‘Grimm’s Words: A Love Letter’ and

in January 2014 he announced he would write no more novels.

In 1954 he married the Swiss dancer Anna Margareta Schwarz with whom he had three sons and a daughter.

They

divorced in 1978 and Grass had two daughters with two different women.

In 1979 he married organist Ute Grunert and they lived near the northern

city of Lübeck, where Grass died on Monday morning from an infection.

Announcing

his death, his publisher Steidl published his last wishes on their

website: “I want to be buried with a sack of nuts and my newest teeth.

If there’s a tumult where I lie then one can gather: it’s him, still

him.”